The Headlamp

👋🐠🧠!

Emma loves headlamps. Every time I give her one her face glows with excitement. Every time, she is surprised.

"Wow! This one has three bulbs, 250 lumens, and seven different settings!" she’ll celebrate. I know each word coming out of her mouth – I bought the thing precisely for those specifications – but I don’t understand a thing. It doesn't matter, her elation gets me high.

Emma is my wife, she is thirty-something years old1 — I won’t add up for you — and I have given her way too many headlamps in our married life. The lamps, all of them, see very little use. However, when a true occasion to use one arises … I mean … that’s a really good day for the whole family.

At this point, anyone not wandering the internet would reflect on Emma’s great capacity for looking at the same object with novelty and excitement. A more intelligent writer would encourage you, "the reader", to bring that fresh look to all the different aspects of your life. Not me, I have been listening to this delicious nu–flamenco for the past few days and a part of me just wants to surrender to melancholy. I want to reflect on the passage of time y decir que el cayo es el dispositivo biológico que mejor expresa la adultez2.

Did I lose you there? I hope not. Por el post anterior deberías saber que el español se me sale cuando la cosa se pone más delicada.3 So yes, a part of me wants to go all “let’s feel alive! untémonos de vida hasta que nos duela la cara.”4 But that’s not where we are headed today. That’s kind of touchy–feely, kind of personal, and you and me reader, we are not there yet.

It is also too literary and this is not a novel nor a book. This is a newsletter. More importantly, that’s not why you are here. I will, in due course, explain – I owe you as much and think you should know – but for now indulge me. Let me tell you where my head is going.

Years of academic learning and critical thinking have crippled me in some ways. Where you see a nice gesture, let’s say giving a new headlamp to Emma to celebrate another random date, I see an implicit contract. Y ya ves, por lo del cayo5 I fully accept that when I give Emma that amazing lamp I researched so carefully on the internet for more hours than I should have, I expect something in return: her honest excitement. Honest is an important word here. Beyond honest excitement I also expect to feel good about myself because of how well I know her. In other words, my ego is unavoidably involved in this contract which Emma inadvertently entered when I decided she’d receive a gift.

What ends up happening most of the time is I cannot just give her the next best lamp which, let's be real, would be the sensible thing to do. No, not me, I have to spend hours of research trying to find the coolest and most obscure lamp out there. This is both because I really want to surprise her — as we have established – but also because I want to express my skill as an internaut. Most of the time I quit this gargantuan task and end up buying something else. Sometimes I persist.

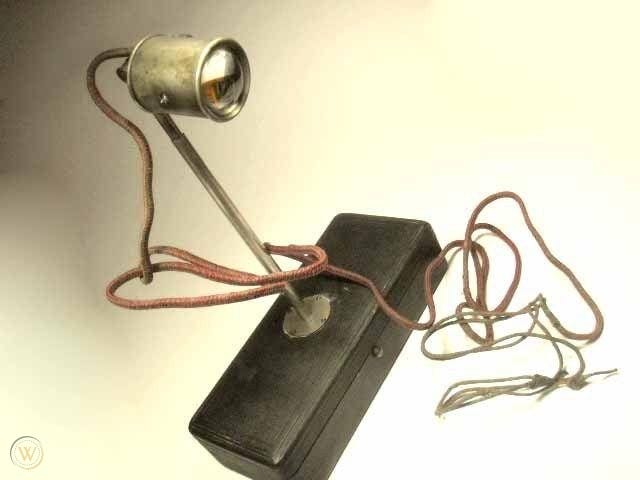

The last time I dived in, I found this:

That's the first commercial headlamp. It was invented and commercialized by the French electrical engineer Gustave Trouvé in 1883. The one in the picture is from the original series. It’s the first piece of wearable electric technology we have a record of. You can imagine my excitement when I managed to get Google to spit out this link to me. This was by far the coolest headlamp a human could buy. I don’t know what Emma would have done with it other than storing it somewhere, but the size of my bragging rights would have lasted till dead did us apart.

Unfortunately, it had already been sold on eBay back in March 2018 for $696 . What a steal! I tried to find the buyer to no avail. I wrote eBay email after email. Nothing worked. I was a little disappointed but it didn’t last. I had found a thread to pull from, an unexpected story.

Besides the headlamp, Monsieur Trouvé also invented an electric tricycle, the first electric light for a boat, the first oxygen suit for balloonists (the coolest invention a human could have ever produced), underwater lighting (used for the construction of the Suez canal), a working electric helicopter, and a long list of other steam–punk–sounding and super cool–looking creations.

As you can expect I spent my fair dose of time researching Trouvé. Was he early? Was he the only one? Was he unique? Sometimes I start googling too fast when a little bit of thinking could give me the answers I’m looking for. Of course he wasn’t the only one. The list of other inventors is impressive. One could spend hours going through each one of them, I know I did.

But after a while you realize that even though everyone gave their inventions a personal touch, they were all trying to solve similar problems in similar ways. And the similitudes don’t end there. The parallelisms between our present–day Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and the Trouvés of the second half of the 19th century are impossible to overlook. Just as I cannot help but tell myself: “of course, Juan, of course, it has all been done before, you’ve seen it happen one hundred times before. And you will see it happen one hundred times again. There’s nothing new under the sun.”

Yet there is something that surprises me. The childish dreams of the Elon Musks of the world haven’t changed much in two centuries. In essence, they probably haven’t changed much in thousands of years

7(👈) And then there is something that bothers me, and something that makes me feel sad. Could it be that damn flamenco again? Maybe, I don’t know 🤷♂️. What bothers me is that our modern billionaires had the script written for them. A portable computer? Yeah, whatever! That was the next logical step after the desktop computer. A phone that’s also a computer? Big deal! All of us that had mp3 players in the 90s knew where things should go. Going to Mars? Yes, of course we want to go to Mars. Do we have the technology to do it? Who doubts it? What do we need? Easy! Rockets that land themselves and robots that can build us a whole habitat so that when we get there everything is ready.

All present problems have been laid out and solved. The fun is over, it is just a matter of time for the engineers to figure the details out. Let them compute and let’s be done with the fucking thing!

I know, that’s too aggressive and I should chill. Y si nos vamos a poner inteligentitos,la pregunta es por qué me caliento por algo tan simple? Pues no sé reader, imagino que tú tienes una explicación si no no preguntarías. Dímela y déjate de joder o vamos pa’lante8. Okay, I am chill now. Here’s what makes me sad, today's’ technological race is cool and all but it lacks oomph and class.

On the other hand, an oxygen suit for balloonists? In 1883? How unscripted and visionary is that! How bohemian!

Well,

Forty–eight years before Trouvé, in 1835, a young Edgar Allan Poe published “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” in the Southern Literary Messenger. I’ll save you the googling and the reading: Pfaal builds a balloon and a device that helps him with pressure and oxygen in order to reach the moon. He then flies off and finds a bunch of cool stuff. In other words, Pfaall builds an oxygen suit for balloonists and finds a whole civilization on the moon.

I haven’t been able to confirm Trouvé read Poe’s story. Maybe he did, maybe he didn’t. I looked for signs everywhere I could. No luck. I think that confirmation is irrelevant though. Sure, it would make this post so much nicer. It would close a loop and it would give me such satisfaction as an internaut. But that’s just my personal need for life to be more literary, to follow the aesthetics of writing and not the rules of reality.

The point is this: once you conceive a possible future then and only then it becomes an option.

Moreover, if that future is plausible that option will be explored. No, I am not trying to bring back Wilde’s life–imitating–art debate. But the fact is, once you can see it, once you visualize Pfaal flying off to the moon in an oxygen suit, then it becomes real in your head. And from the perspective of your brain, real-in-your-head and real are the same thing. Because these are just ideas. They are biological products of the exact same nature, no matter how abstract they are, no matter how metaphysical.

They are biochemical connections of our system, they don’t exist outside us. Their reality is independent of the reality of what they represent.

The idea of a pink unicorn is real whether it exists or not, and it is the same as the idea of a cow. And precisely because ideas are biological products they can spread like viruses. Sure, whether the virus analogy works can and has been debated, but that amount of specificity isn’t important. What matters is that some ideas, the plausible ones, the graphic ones, the well–written ones become memes and live in the collective web of biological products that is culture.

And that’s how we get from Poe to Trouvé. Not because he read him, but because in the memes of the time the idea of an oxygen suit for balloonists had already been spread, it already existed, the dots had been connected. And once the idea was conceived the possibility existed.

Yup, just like that. So long Monsiour Gustave Trouvé! 👋 You are nothing but just another restless kid with electric dreams and a talent to shut down the naysayers. You just figured out the details that somebody scripted for you a while ago. No oomph, no class.

There’s one fun story, though, that makes me really happy — it cannot all be bad news in this second post.

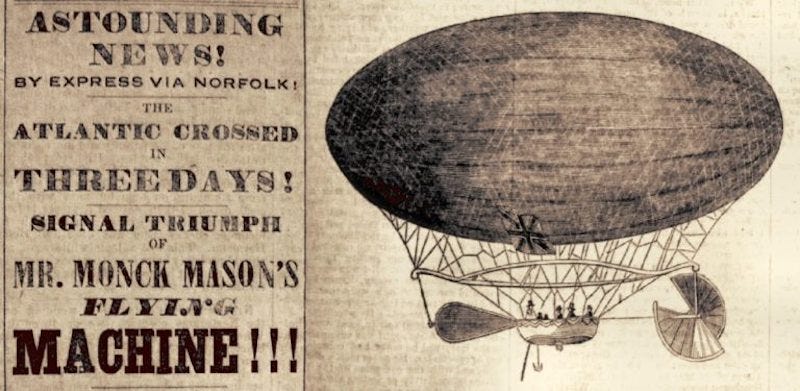

Poe created a wonderful hoax appropriately named the Balloon–Hoax. In 1844, New York’s newspaper The sun published an extra edition celebrating the completion of the first transatlantic balloon flight. Allegedly, European balloonist Monck Mason had flown across the Atlantic Ocean in 75 hours, starting in Norfolk and ending in Sullivan’s Island, North Carolina. The article included a graphic of the balloon’s design among all the details and technicalities of the flight.

When published, most people believed it to be true because it came in the regular newspaper, it was written to be believable, and because it was plausible. I mean, they did an extra edition just for the thing. The afternoon the story broke, hundreds gathered by The Sun’s press to hear everything about it.

Paperboys made a lot of money selling overpriced copies, other newspapers made money re–printing the story. Some people were excited, some people panicked, and in general the public fought over the whole thing because that’s what the public does. This reception was way more intense than Poe anticipated and the paper had to retract the story two days later.

Yes, reader, I am with you. How did the paper allow this? Well, it was an extreme publicity stunt that evidently worked pretty well. But there’s more to it. And this brings us to the 5th juncture of this post: by this point you already know that this too had been scripted and laid out, and you are trying to hurry me up to get to the point. Well, yes, you are both brilliant and right, although quite annoying. This hoax was a response to a previous one appropriately called the Great–Moon–Hoax.

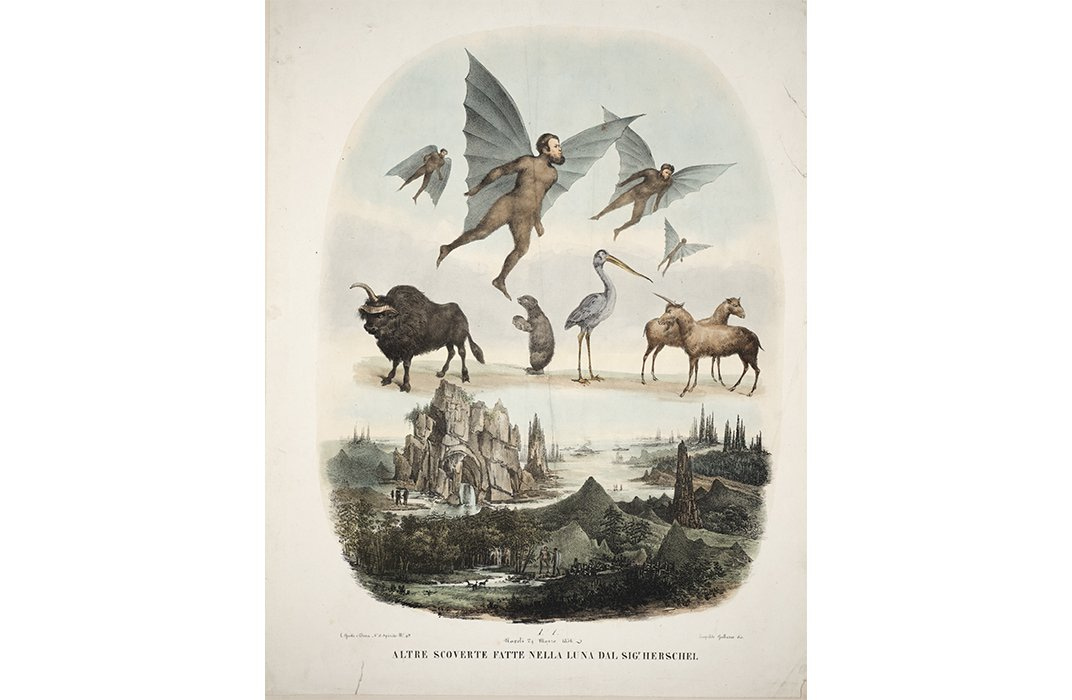

In 1835, the same year Poe published the unparalleled adventure of Pfaall, The sun had published the genius and grandiose story of the discovery of a complete civilization on the moon by someone else. Richard Adams Locke was the author and the story was fantastic. Locke was smart enough not to sign it with his name, instead, he gave authorship to Dr. Andrew Grant, companion of famous astronomer Sir John Herschel.

Grant was full–on fiction, but Herschel was very real. Sir John had discovered four galaxies: NGC 7, NGC 10, NGC 25, and NGC 28. And no, he didn’t give them these atrocious names, those were the product of boring professors of the 20th century. But he did name seven of Saturn’s moons: Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan, and Iapetus. Those, of course, are names with some kind of oomph and class.

Anyhow, in the hoax Grant claimed they had built a new telescope with advanced technology and reported they had found a whole civilization on the moon. There were bison, goats, unicorns, bipedal tail–less beavers, and bat–like winged humanoids.

Did people believe it? You bet your ass they did. For the same reasons you believe what you believe and Q–Anon is a thing. But they didn’t believe it as hard as they believed the balloon hoax. Locke had pushed it a little too far.

Now, this is where the whole thing gets tangled and where it all starts to make sense. Poe was really mad at Locke. He truly believed that Locke had based his hoax on Pfaall’s story. You cannot blame him, the accusation made sense. So Poe wanted to get back at Locke by creating a better hoax, and so he did. He went all the way, and then some, and it got a little out of hand, as things tend to get when the writing is good and spirits are high. He made the balloon hoax, which brings us back to Pfaall, and then back to Poe again.

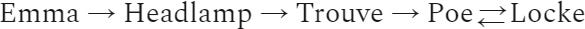

Great, now we are in a loop, which is truly our main juncture. Here’s our storyline so far:

I agree the graphic is cheap and there is no time to waste. We are also literally just going round in circles. Let me get us out. Remember when I said I would tell you why you are here? That was me saving my ass and being smart. You always have to leave yourself some crumbles to come back to.

But here’s your answer, the result of my wanderings on the internet. The arrows you see up there are the map of my wandering. The links exist. And while there is HTML code taking you from one place to the next, the links only really become active when you think about them.

Code is dead after all. Only after you read these lines and your neurons connect the electrical pathways created by these textual events the graph is connected, only when it becomes a biochemical product it becomes real. Otherwise, those links will never be active.

Now, those links can be activated because the architecture of the internet allows them. The net holds the nodes and I connected them in that particular order. I don’t know why, but no matter the reason I have to stop blaming the flamenco. Now that you read this, you have connected them again, which is cool. And this newsletter is me being audacious and making a bet. I bet you I can keep making you read my internet wanderings. I bet you and I can keep them links alive somewhere. In the end, my hope is we can connect and I can show you how my brain works. Not because I think is any different than any other brain. Because I spend so much time alone inside of it, and if I don’t get all these things out, they will die with me, and that seems like a waste. And if I manage to get you with me to the very end of this project, well, I can only say it like this: points will be made, hearts will be broken, laughs will be had, and things will get very real.

Hush, reader, I am not done. I agree with you that that’s a low rhetorical move and a relatively cocky bet. It was both arrogant and as dorky as you can get. Also a little touchy-feely. Again, you are right. But if you are a reader of any worth you should know that this was scripted too, it had all been laid out before.

The story is called “The Machine Stops” by E.M. Forster and it was published in 1909. It describes a world in which the machine takes over all basic maintenance functions of humanity. In many ways it’s everybody’s dream: the machine provides the food and cooks it; the machine takes care of the cleaning; the machine deals with the production of energy and goods; the machine handles transportation, housing, medicine; the machine is the government; the machine does it all, even its own maintenance.

You, my dear reader and friend, are always asking the entrepreneurs of the world to stop with the nonsense of Mars and instead hurry up with beefing up the roombas and the dishwashers and the self-driving cars so that you don’t have to do any more of that. Well, Forster panned it out for you. In the fictional world he created the machine takes care of it all, every little thing.

His stroke of genius is that he doesn’t do the cheesy Matrix scenario in which the evil robots turn against humans, which is always a bad fictional move by writers that don’t understand computer code. Don’t get me wrong, I consume those narratives like they are buttery popcorn for my brain, but Forster’s move is more elegant and premonitory.

In his world, humans would become producers and consumers of second-hand ideas. Let’s be precise: they become exclusively that. They will mostly stay up in their rooms, communicate via digital mediums, and become isolated individuals connected to others only through discourse. Just blah, blah, blah, and nothing else. Suena familiar, no? Un poco sí.

All sci-fi of any worth is the product of somebody’s anxiety of a plausible future. Forster’s consists in the clever assertion that, when you remove from the human condition the need to work, to move, and to complete the most quotidian of tasks, human existence is reduced to the continuous spilling of each individual’s inner brain chatter out into the world. Life becomes this atrocious overanalyzed, rehashed, and rationalized reality made out of nothing but ideas.

I know you’re trying to resist this! “That’s not what would happen Juan! That’s so exaggerated, it’s absurd. Forster is wrong! Humans would find a way to thrive in that context!” Claro reader, tienes toda la maldita razón. Forster pudo haber resuelto la cosa de millones de formas distintas. Y tú por supuesto no estás satisfecho con su modo y propondrías un mundo radicalmente distinto. But that’s what makes storytelling brilliant.

A story is not a logical sequence of events with a prescribed relationship between them. Repito: it is not a series of episodes that follow logically from the rules of creation of the universe in place. But when the writing is good, any event can be connected and understood. That’s why, when you read Forster’s story, reader, you would not be battling with him like you are with me now. Because in my retelling of his novel I took out all the meat and left you with the bones, so all you see is the arrows, the naked connections, void of oomph and class.

When the story is narrated nicely it feels like life. It feels like there is logic to the sequence of events. It couldn’t have happened any other way is what it feels like. Then, and only then, you start thinking, “Damn Forster! He saw the internet and social media before they were even close to being alive. The tragicomedy of the human condition is that we are all just passing time here on earth. When you remove the need to do from all of us, we are left with nothing.” Well, seamos honestos reader, tú a pesar de tu inmensa inteligencia no eres tan elocuente, pero digamos que pensarías algo similar.

Then you can draw parallels to your current life and realize that all those chores you love to hate and that Monday walk your doctor keeps prescribing aren’t the things getting in your way of accomplishing what matters. Those are the things that matter, they are life my reader friend.

The point is that you cannot isolate yourself and pretend to live off of your ideas because ideas, as we said, are biological products. If you want to get nasty let’s go there. Ideas are biological secretions and, if you live in a world in which you have disregarded the biological entity that produces them from its biological needs, your ideas get … well, stupid. When the connections between the dots in your head are void of any referential entity outside your brain, or other people's brains, they don’t matter any more.

It cannot all be pink unicorns and ballon hoaxes, it cannot all be civilizations on the moon. At some point, we have to come back to the physical reality of our being.

The other side is also true. When we strip our lives from everything that needs doing, all we are left with is that inner chatter, that need to connect the dots, to hash and rationalize ideas, and to turn everything into a story. Because that is at the core of who we are. That is us.

That’s why you need Poe, and art and philosophy and connection. This is the reason why the arrows of the graph matter. That is what unites us in our shared humanity, as well as what allows us to express our uniqueness. And it is also why you made it all the way to the end of this post - and how I like to justify this and my future wanderings.

That is it. It is upsetting how close Forster’s story is to the future, to the restless silicon kids with their electrical dreams. And it is wonderful, exactly because of this. Like that effing flamenco. Tú me dejaste de querer cuando menos lo esperaba. Cuando más te quería. Se te fueron la' gana'.

At this last juncture we have closed all the loops but one, Emma. And we will leave that one open like that, because that last arrow will just point to me. And as I said before dear reader, you and me, we are not there yet. We will be, but not today.

Till the next post dear 🐠🧠!

She was when I wrote this post. Now that I publish, she is forty-something.

Literally, it translates to: “and say that the calluses are the biological device that best expresses adulthood.” It is really a choppy construction. In English it sounds pretty bad, in Spanish it’s cleverer. Some might say that *analogy* would be a better word here than *biological device* which is heavy and clumpy. But I like the implications, so please dear reader, I have enough with the shouting in my own head.

According to Google Translate: “From the previous post you should know that Spanish comes out when things get more delicate.” I would have never translated it like that but there is something animalistic about the Spanish coming out of me, something like a visceral force I cannot control. That’s fitting, with me and with the language of my elders. I like that. We’ll keep it.

When I wrote this, I thought for a while: cómo traducir esto pa’ que lo entienda un humano cualquiera en cualquier lugar del mundo después de tomarse un vaso de agua un martes por la mañana. Pero me rendí. Porque eso que es untarse de vida me parecía como tan latinoamericano, como tan sudaca, como que se necesitaba esa conjunción de felicidad inocente y malparidez existencial que en el sur producimos en todo lo que hacemos. And so I stopped trying. Initially I wrote here a lazy: “untraslatable”. But then Caro said this:

Touché! There you have it. You do with that whatever you can, I want to do more but this is the only fair thing to do with this brilliance.

Okay, yo sé, yo sé, quién carajos es Caro? I really don’t know. If you paid attention to the last post you would know she is the editor, that is all I can say. You think she is invisible because I work hard to make my voice pretty loud, and she is superb at her job. But Caro has read every word I wrote with generosity and depth. She is the ultimate reader, an updated version of yourself. Let’s say it like this: when I sound good dear reader, you can thank her. Ah, sí, sí, sí reader! Por qué presentarla de esta manera tan torpe en un piedepágina? Well, it seemed like the right place. Pero tomátelo con calma, you will hear more from her in due time.

Too much cleverness already, let’s keep it simple this time: “And so you see because of the calluses thing.”

Here Emma would say “Hey yooo!” This is too raunchy for this newsletter’s body. Not for the footnotes. The footnotes are where we will deal with all the dirty things, that’s why they exist. Footnotes are the literary equivalent of the “under the table” thing.

I know the ellipsis here is funky, reader! But I need a breather without changing paragraphs. I just do. Sometimes you talk like a boomer. Yup, we millennials use the ellipsis way more than previous generations. It is alright if you think this is wrong. You spent several years in the education system getting, well, schooled. Those rules became part of your identity. This is the correct way to do this. They allowed you to express yourself more clearly because standardization helps communication. But they also allow you to separate yourself from the ones that don’t know those rules, the ignorant, the uneducated. Or better, they allowed you to separate yourself from the degenerates that don’t care about them. That’s why this might bother you. But sweat not reader, the following generations will do something similar to us millennials and, in their own way, they already are.

Make an effort.

Muy entretenido profe, y looking forward to find out what happend con la lámpara de Ema